Salar de Uyuni – A Picture is Worth a Thousand Words…

The highlight of any trip to Bolivia has to be the Salar de Uyuni. At 20,000 km² the world’s largest salt pan is an awesome sight to behold. A visit to Uyuni’s flooded salt pans, lakes and cacti covered islands will make you feel as if you have landed on another planet. Let the photos speak for themselves:

Digging in Potosi – The tale of dust, dynamite and Bolivian Whisky

Although the silver is depleted, the Cerro Rico is still being mined for composito a mixture of tin, mercury and other metals. Miners are organized in collectivos, i.e. they get together and work the mine as (in a way) entrepreneurs. This, however, happens with primitive technology: dynamite, pneumatic hammers (sometimes) and most commonly manpower. Many miners start working at the age of ~12, but do not live past 35 because of Silicosis, a lung infection caused by the excessive intake of dust that eventually destroys the lungs from the inside. Their fate is profoundly explored in the documentary ‘The Devil’s Miners‘ by Richard Ladkani and Kief Davidson, which follows two pre-pubescent brothers working in the Potosi mines.

Although the silver is depleted, the Cerro Rico is still being mined for composito a mixture of tin, mercury and other metals. Miners are organized in collectivos, i.e. they get together and work the mine as (in a way) entrepreneurs. This, however, happens with primitive technology: dynamite, pneumatic hammers (sometimes) and most commonly manpower. Many miners start working at the age of ~12, but do not live past 35 because of Silicosis, a lung infection caused by the excessive intake of dust that eventually destroys the lungs from the inside. Their fate is profoundly explored in the documentary ‘The Devil’s Miners‘ by Richard Ladkani and Kief Davidson, which follows two pre-pubescent brothers working in the Potosi mines.

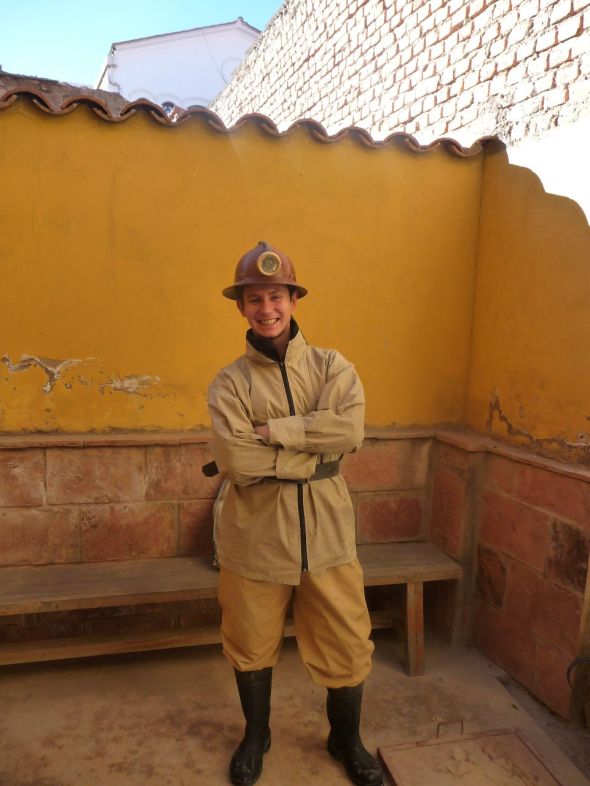

Although miners know that working in their mines will hasten their deaths they exhibit a certain pride in the fact that they are miners and that they are working for themselves. As I found out when I visited their mine, the most outstanding and breathtaking tourist attraction in Potosi. I explored an active shaft, saw the dynamite being planted and exploded, helped with drilling the dynamite holes and more. As this was not for the claustrophobic or faint hearted Michelle and I decided that I should have my boys’ adventure alone.

Although miners know that working in their mines will hasten their deaths they exhibit a certain pride in the fact that they are miners and that they are working for themselves. As I found out when I visited their mine, the most outstanding and breathtaking tourist attraction in Potosi. I explored an active shaft, saw the dynamite being planted and exploded, helped with drilling the dynamite holes and more. As this was not for the claustrophobic or faint hearted Michelle and I decided that I should have my boys’ adventure alone.

After getting our overalls, boots and hard hats, the tour started with the purchase of gifts for the miners: Bolivian whisky (98% alcohol), orange juice (to clear the throat after drinking the whisky), coca leaves (to numb hunger, thirst and fatigue), and gloves. Soon thereafter we drove to the entrance of the mine and descended down one of the many holes in the mountain.

After getting our overalls, boots and hard hats, the tour started with the purchase of gifts for the miners: Bolivian whisky (98% alcohol), orange juice (to clear the throat after drinking the whisky), coca leaves (to numb hunger, thirst and fatigue), and gloves. Soon thereafter we drove to the entrance of the mine and descended down one of the many holes in the mountain.

The rest of the tour was indescribable; something one has to experience on his /her own. Walking hunched through the tunnels, experiencing the noise of oxygen pumps, the mud, the dust and everything else constitutes an attack on the senses that most of us in the developed world rarely experience. Seeing the miners work with techniques that have been in use for 100 years or more is unbelievable.

The rest of the tour was indescribable; something one has to experience on his /her own. Walking hunched through the tunnels, experiencing the noise of oxygen pumps, the mud, the dust and everything else constitutes an attack on the senses that most of us in the developed world rarely experience. Seeing the miners work with techniques that have been in use for 100 years or more is unbelievable.

The tour is extremely immersive as tourist barriers or safety nets do not exist. Warped wooden planks are used as bridges over gaping holes that stretch into an indefinable darkness. Self-made ladders resembling those kids might make to access a tree house are standard, but only for a quarter of the way, for the rest you have to climb a rope. And every now and then you hear and feel the distant bass thump of a dynamite explosion, 5000 of which occur within the mountain every day.

The tour is extremely immersive as tourist barriers or safety nets do not exist. Warped wooden planks are used as bridges over gaping holes that stretch into an indefinable darkness. Self-made ladders resembling those kids might make to access a tree house are standard, but only for a quarter of the way, for the rest you have to climb a rope. And every now and then you hear and feel the distant bass thump of a dynamite explosion, 5000 of which occur within the mountain every day.

Miners sometimes put in shifts of 24h straight, in which they drill dynamite holes, fill them, explode the dynamite and take-out the composito mining carts, over and over again. The only way to survive this is alcohol and coca. All miners have a huge bubble on one of their cheeks, resembling some kind of terrible tumor. This is a bulk of coca leaves they suck on to suppress thirst, hunger and fatigue. Additionally, everybody is drinks alcohol on duty. We were also invited to partake in the consumption of Bolivian whisky whenever a group of miners took a break.

Miners sometimes put in shifts of 24h straight, in which they drill dynamite holes, fill them, explode the dynamite and take-out the composito mining carts, over and over again. The only way to survive this is alcohol and coca. All miners have a huge bubble on one of their cheeks, resembling some kind of terrible tumor. This is a bulk of coca leaves they suck on to suppress thirst, hunger and fatigue. Additionally, everybody is drinks alcohol on duty. We were also invited to partake in the consumption of Bolivian whisky whenever a group of miners took a break.

The highlight of the tour was actually drilling dynamite holes in a shaft using a pneumatic driller (an easy going 80kg heavy). Again the dust, noise and exertion cannot be described but have to be experienced. The only thing I can say is that we were absolutely exhausted after drilling 2 holes (which probably took us 15 minutes each), and now imagine that you have to do that day in, day out for several hours.

The highlight of the tour was actually drilling dynamite holes in a shaft using a pneumatic driller (an easy going 80kg heavy). Again the dust, noise and exertion cannot be described but have to be experienced. The only thing I can say is that we were absolutely exhausted after drilling 2 holes (which probably took us 15 minutes each), and now imagine that you have to do that day in, day out for several hours.

The tour closed with a visit to the Tio, who owns the Cerro Rico, this ‘devil’ is the invisible power that can take or spare lives when working in the mines. Consequently, all miners make sacrifices to the Tio and spill whisky on the ground every time they drink. This superstition is deeply rooted in the community and although they are Catholic, they believe that Jesus’s power does not extend underground beyond the mine entrance. This belief is comes from colonial times and was invented by the Spaniards who told indigenous people that they had to work otherwise the Dio would get them. Since in Quecha, the local language, no sound for ‘d’ exists the Dio became Tio.

Potosi – The town with a silver lining

As a teenager I had heard of the infamous mines of Potosi, where indigenous and African slaves were used to exploit silver for the Spanish crown. Being in Bolivia I convinced Michelle to seize the opportunity to visit this city.

As a teenager I had heard of the infamous mines of Potosi, where indigenous and African slaves were used to exploit silver for the Spanish crown. Being in Bolivia I convinced Michelle to seize the opportunity to visit this city.

Situated at around 4100m above sea level, Potosi is the highest city on earth, and thus it literally takes your breath away, due to the lack of oxygen. Despite a gradual ascent through the Andes, we struggled to walk 1 km with our backpacks on when we arrived – what usually might have taken 15 minutes, took the better part of 30. Afterwards, we tried to make the most of the remaining sunshine but had to retire to a restaurant to have food and catch our breath.

Although Potosi is not particularly large (~180.000 people), it has a rich history and beautiful colonial architecture as it was once one of the richest cities in the world. This wealth stemmed from the silver the Spaniards extracted from the Cerro Rico (rich mountain) after colonizing this region. During 1556-1783 a total of 41.000 tons of silver were extracted in Potosi alone. Thus it became a magnet for adventurers, New World aristocrats, and artists, all seeking to benefit from the riches of Potosi and its population swelled to more than 200.000 (comparable to the size of London at that time). The fact that a whooping 86 churches were built in that period is another sign of that wealth.

By 1825 the silver was almost depleted and the population sank to a mere 10.000. In a way Potosi could be compared to places like Dubai, or Qatar, that achieved extreme riches because of a natural resource, and thus became a magnet for people from all over the world, but eventually faced the threat of obscurity once the resource was depleted. The only hope of the UAE and states like it is to successfully reinvent itself.

Another breathtaking site and hint of former wealth in Potosi is the Casa Nacional de la Moneda. Praised by the Lonely Planet as “being worth its weight in silver”, it is housed in one the largest colonial buildings in Bolivia, and was formerly used as a mint.

It displays colonial art, silver coins and silverware, as well as the different technologies used to process silver. Two coins displayed in the museum are from a galleon, the Nuestra Senore de Atocha, that sank off the coast of Florida in the US en route to Spain in 1622 and was discovered by the Americans in 1985. It was filled with silver bars and coins worth 440 million USD. Unfortunately, Bolivia, South America’s poorest country, only received a meager ‘donation’ of two coins, both of which are now on display in the museum.

This silver has another even darker side: The suffering and deaths of the indigenous and black African slaves used to extract the silver from the mines of Potosi. Spaniards never actually entered the mines, or got their hands dirty, instead they used a system of forced labour called mita, in which Indigenas were forced to ‘donate’ two months of the year to work in the mines. Sometimes these two months turned into four or six months, or as long as one survived. Forced to work shifts of 16h hours, with nothing but their bare hands, or primitive tools, some did not see daylight for days and most did not survive long. An estimated 8 million people are thought to have died in the mines of Potosi; the primitive conditions, use of child labor and deaths continue to this day.

Visiting the Mennonite Communities in Filadelfia, Paraguay

On discovering that there was a German speaking community of Mennonites living in the middle of the Chaco we simply had to visit. Getting to Filadelfia, the largest and most important of the Mennonite communities in the Chaco, is easier today now that there are two buses a day which make the eight hour journey from Asunción, the capital of Paraguay. However, even a brief glance at the map will show that Filadelfia really is in the middle of nowhere; the journey reinforces this in the mind of the every passenger as the bus bumps its way along the sandy road bordered one either side by unbroken Chaco and few inhabitants as far as the eye can see.

On discovering that there was a German speaking community of Mennonites living in the middle of the Chaco we simply had to visit. Getting to Filadelfia, the largest and most important of the Mennonite communities in the Chaco, is easier today now that there are two buses a day which make the eight hour journey from Asunción, the capital of Paraguay. However, even a brief glance at the map will show that Filadelfia really is in the middle of nowhere; the journey reinforces this in the mind of the every passenger as the bus bumps its way along the sandy road bordered one either side by unbroken Chaco and few inhabitants as far as the eye can see.

Who were the Mennonite settlers who settled in this ‘Green Hell’? There are actually two main groups which belong to the Mennonite community in Paraguay: The first is comprised of pacifist Christians of German descent, who moved to Paraguay from Canada in the 1920s; they wanted to maintain their religious freedom and the ability to educate their children in German, rather than in English as the government of the time had requested. The other group was made up of the descendents of Russians who first fled the upheavals of Bolshevik Russia and Stalin’s subsequent purges. One Mennonite we met told us the story of her deaf father who had escaped Russia with her mother and made the long journey to Paraguay in search of a better life.

Who were the Mennonite settlers who settled in this ‘Green Hell’? There are actually two main groups which belong to the Mennonite community in Paraguay: The first is comprised of pacifist Christians of German descent, who moved to Paraguay from Canada in the 1920s; they wanted to maintain their religious freedom and the ability to educate their children in German, rather than in English as the government of the time had requested. The other group was made up of the descendents of Russians who first fled the upheavals of Bolshevik Russia and Stalin’s subsequent purges. One Mennonite we met told us the story of her deaf father who had escaped Russia with her mother and made the long journey to Paraguay in search of a better life.

At the Jakob Unger Museum on Ave Hindenburg it is possible to see some of the numerous items which settlers brought from Europe to Paraguay and to see photos depicting the conditions under which they lived in the first decades after the settled. Other items of interest include an example coffin made from a hollowed out tree trunk, the printing press used to produce the local newspaper and money from the period of the early waves of immigration. In a separate building an impressive collection of taxidermy including a puma, an anteater, local birds and reptiles is also on display.

At the Jakob Unger Museum on Ave Hindenburg it is possible to see some of the numerous items which settlers brought from Europe to Paraguay and to see photos depicting the conditions under which they lived in the first decades after the settled. Other items of interest include an example coffin made from a hollowed out tree trunk, the printing press used to produce the local newspaper and money from the period of the early waves of immigration. In a separate building an impressive collection of taxidermy including a puma, an anteater, local birds and reptiles is also on display.

Like the first settlers in America, the Mennonites were attracted by the opportunity for self determination and the chance to cultivate land which they received from the Paraguayan government. Photos in the Koloniehaus, which now houses the Jakob Unger Museum, document the history of the Mennonites – proud Europeans wearing the unsuitable winter garments as they pose for photographs in the overgrown Chaco. The tropical heat, disease carrying mosquitoes, snakes, pumas and jaguars as well as the lack of potable water must quickly have put the notion that they had reached the promised land out of their heads – over time they dubbed the Chaco the ‘Green Hell’ because of its razor sharp vegetation, which, if not carefully removed, could cause desertification, rendering the land useless. Another issue was the extreme temperature fluctuations which the region is prone to.

To this day, although the Chaco covers more than two thirds of Paraguay, only 2.5 % of the population currently reside there. However, with the completion of the Trans-Chaco Highway, which now provides a vital link to neighbouring Bolivia, tourists and job seekers from other parts of the country, as well as those looking to escape the drug-fuelled crime in eastern Paraguay have started arriving. Previously, there was limited contact with the outside world: Paraguayans did not choose to visit this inhospitable environment – this was a place of exile for opponents of the government and the location of the Chaco War, but aside from that the settlers managed to maintain a traditional lifestyle in keeping with their beliefs and values.

To this day, although the Chaco covers more than two thirds of Paraguay, only 2.5 % of the population currently reside there. However, with the completion of the Trans-Chaco Highway, which now provides a vital link to neighbouring Bolivia, tourists and job seekers from other parts of the country, as well as those looking to escape the drug-fuelled crime in eastern Paraguay have started arriving. Previously, there was limited contact with the outside world: Paraguayans did not choose to visit this inhospitable environment – this was a place of exile for opponents of the government and the location of the Chaco War, but aside from that the settlers managed to maintain a traditional lifestyle in keeping with their beliefs and values.

On arrival in Filadelfia, it is easy to see why poorer Paraguayans are attracted to the Germanic order of Filadelfia with its rubbish free streets, which lack the ubiquitous stray dogs seen in other large towns; the grid-like plan of the town with its wide roads, large houses and prosperous farms makes for a strikingly calm contrast to Asunción and Encarnation.

On arrival in Filadelfia, it is easy to see why poorer Paraguayans are attracted to the Germanic order of Filadelfia with its rubbish free streets, which lack the ubiquitous stray dogs seen in other large towns; the grid-like plan of the town with its wide roads, large houses and prosperous farms makes for a strikingly calm contrast to Asunción and Encarnation.

In town the contrast between the cars and houses of the Mennonites compared with those of the indigenous people as well as the wealth of supplies available at the Fernheim co-operative supermarket, as opposed to the basic staples on offer in the shops owned frequented by the indigenous population are reminders of how unequal the wealth distribution in the area is. When questioned about this the German Mennonites we talked to argued that their parents and grandparents had come to this place which nobody else had wanted to inhabit and created all of their wealth from scratch.

In town the contrast between the cars and houses of the Mennonites compared with those of the indigenous people as well as the wealth of supplies available at the Fernheim co-operative supermarket, as opposed to the basic staples on offer in the shops owned frequented by the indigenous population are reminders of how unequal the wealth distribution in the area is. When questioned about this the German Mennonites we talked to argued that their parents and grandparents had come to this place which nobody else had wanted to inhabit and created all of their wealth from scratch.

The curator of the Jakob Unger Museum and a local shop keeper explained (in excellent German) that the recent interest that Filadelfia has attracted has not necessarily been positive. There is concern that limited availability of jobs may lead to crime and other social problems, they also mentioned that although most of the community is now fluent in Spanish, in order to maintain their culture and traditions they would like to employ people who speak German. Given that the number of tourists who visit the area is relatively small, they are not seen as posing a threat to the Mennonite way of life. If one looks at the way people dress, observes the strikingly blonde Mennonite teenagers making their way to and from school and watches the local TV stations (which include live broadcasts of cattle auctions from around the country!), is clear that Filadelfia is being increasingly influenced by the outside world.

Five Things You Probably Didn’t Know About Paraguay

Paraguay? Why Paraguay? It seems that everyone you tell asks those two questions at some point because the general consensus among travellers in South America seems to be that Paraguay, rather like Suriname and the Guyanas is of minimal importance in comparison with other countries on the continent because it lacks major attractions such as Machu Picchu, Salar de Uyuni or Buenos Aires.

1. Paraguay is the second poorest country on the continent after Bolivia and the gap between the wealthy and the rest is quite striking. Driving through the country it is possible to see palatial villas and brand new SUVs, which contrast starkly with the rickety public transport system and the large number of buildings which look ripe for demolition. The unequal distribution of wealth in the country has also been the cause of land seizures by indigenous groups.

2. Like us you may find Paraguayans pretty difficult to understand because they seem to mix their Spanish and Guaraní in conversation (this mixture is known as Jopará). Among the Mennonite communities in the Chaco, German (Hochdeutsch and Plattdeutsch) is still spoken.

3. Paraguay is home to Trinidad and Jesús, two of the least visited Unesco World Heritage Sites on the continent. Trinidad is the best preserved of the two sites and is easily visited by bus from Encarnatión. The Jesuit ruins are set on a lush green hill in the middle of a small village and because there are so few visitors you can pretty much have the whole place to yourself.

4. The world’s largest water reserve, the Acuifero Guaraní, lies under Paraguay (and parts of Brazil and Argentina) and the Chaco, also known as the ‘Green Hell’, makes up more that 60% of Paraguayan territory, however less than 3% of the population lives there, most of whom are indigenous, as well as the descendents of Canadian and Ukrainian-German Mennonites.

4. The world’s largest water reserve, the Acuifero Guaraní, lies under Paraguay (and parts of Brazil and Argentina) and the Chaco, also known as the ‘Green Hell’, makes up more that 60% of Paraguayan territory, however less than 3% of the population lives there, most of whom are indigenous, as well as the descendents of Canadian and Ukrainian-German Mennonites.

5. In recent years Paraguay has attracted interest from outsiders because of its reputation for producing beef (as we learned when we turned on the TV one day to find that there was a channel dedicated to cattle news and broadcasting auctions!) and for the potential profits which soybean farmers, who are facing increasing prices for arable land in Argentina and Brazil, hope to make by relocating there. President George W. Bush Jr. is also rumored to have purchased an estate in the country in 2006.

5. In recent years Paraguay has attracted interest from outsiders because of its reputation for producing beef (as we learned when we turned on the TV one day to find that there was a channel dedicated to cattle news and broadcasting auctions!) and for the potential profits which soybean farmers, who are facing increasing prices for arable land in Argentina and Brazil, hope to make by relocating there. President George W. Bush Jr. is also rumored to have purchased an estate in the country in 2006.

Four Left Feet: Sometimes It Takes More Than Two To Tango…

It seems like just yesterday that we were standing on the border between Thailand and Laos trying to get a lift into town with a local who we had mistaken for a taxi driver. That was January, now suddenly it was the end of June. Out of the blue, my birthday had snuck up on me, on us, and so Martin was tasked with trying to make one particular day in what felt like and endless string of memorable days even more special. So what did he do? He decided to book a tango lesson.

It seems like just yesterday that we were standing on the border between Thailand and Laos trying to get a lift into town with a local who we had mistaken for a taxi driver. That was January, now suddenly it was the end of June. Out of the blue, my birthday had snuck up on me, on us, and so Martin was tasked with trying to make one particular day in what felt like and endless string of memorable days even more special. So what did he do? He decided to book a tango lesson.

I must admit that on hearing that my birthday present was going to include a dancing lesson I was tempted to protest, to feign illness, arrive late, or to do all three. I kept mentally fast-forwarding to a mirrored dance studio, which magnified my every mistake. I imagined an over eager teacher chastising me for not being able to replicate the arrogant elegance of the tango and disapproving of my flat pumps. My trepidation, which must emanate from a suppressed childhood ballet trauma, was palpable, but I need not have worried.

Our tango lesson at Complejo Tango turned out to be one of the most hilarious things I have done in a long time. The class had an unusually large number of male participants including a rugby team which was on tour in Argentina. Our effeminate instructor wasted no time whipping the motley crew of would be tango dancers into shape. The group included a trio of Japanese women in hiking boots, a rugby player in a bright pink pair of pyjamas who appeared to have lost a bet with the boys, and several haughty Brazilians, who were clearly perplexed by the lack of rhythm emanating from certain corners of the room.

Our tango lesson at Complejo Tango turned out to be one of the most hilarious things I have done in a long time. The class had an unusually large number of male participants including a rugby team which was on tour in Argentina. Our effeminate instructor wasted no time whipping the motley crew of would be tango dancers into shape. The group included a trio of Japanese women in hiking boots, a rugby player in a bright pink pair of pyjamas who appeared to have lost a bet with the boys, and several haughty Brazilians, who were clearly perplexed by the lack of rhythm emanating from certain corners of the room.

Most of us spent the entire hour crying with laughter, as our instructor critiqued our attempts to repeat the steps and tried to resist the temptation to smile when mimicking the sultry poses which tango demands.

By the end of the lesson all the women had learned to surrender into the arms of their male partners and a photo session ensued in which we attempted to capture high kicks, arched backs and head rush inducing positions on camera.

By the end of the lesson all the women had learned to surrender into the arms of their male partners and a photo session ensued in which we attempted to capture high kicks, arched backs and head rush inducing positions on camera.

Next, it was off to a three course dinner with copious amounts of wine from Mendoza, followed by a show performed by professional tango dancers. The show took us on a jaunt through the history and development of tango from its early origins to its current day revival. The live band featured haunting violins, an accordion and a perfectly postured pianist who played various styles of tango music over the next hour and a half.

Next, it was off to a three course dinner with copious amounts of wine from Mendoza, followed by a show performed by professional tango dancers. The show took us on a jaunt through the history and development of tango from its early origins to its current day revival. The live band featured haunting violins, an accordion and a perfectly postured pianist who played various styles of tango music over the next hour and a half.

The spinning, flipping and high kicks were effortlessly executed, but knowing how difficult it had been for all of us to master the most basic of tango steps, such as the ochos (named after the number eight in Spanish because it requires the female to make move in a figure of eight), we watched as the dancers with respect and envy as they glided athletically across the stage, changing costumes and scenes countless times to perform an awe inspiring show.

The spinning, flipping and high kicks were effortlessly executed, but knowing how difficult it had been for all of us to master the most basic of tango steps, such as the ochos (named after the number eight in Spanish because it requires the female to make move in a figure of eight), we watched as the dancers with respect and envy as they glided athletically across the stage, changing costumes and scenes countless times to perform an awe inspiring show.

Urban Uruguay – Uncovering the Most Underrated Capital City in the Region

Montevideo is an odd mix of beautiful plazas and pedestrian zones abutting some seriously depressed neighbourhoods. These multifaceted neighbourhoods host corporate offices, government buildings and the derelict graffiti covered relics of colonial splendor. In Ciudad Viaje, the graffiti is an incoherent salute to the poor and a desperate cry for liberation from gentrification, a ubiquitous and seemingly unstoppable force; construction and restoration are everywhere.

Montevideo is an odd mix of beautiful plazas and pedestrian zones abutting some seriously depressed neighbourhoods. These multifaceted neighbourhoods host corporate offices, government buildings and the derelict graffiti covered relics of colonial splendor. In Ciudad Viaje, the graffiti is an incoherent salute to the poor and a desperate cry for liberation from gentrification, a ubiquitous and seemingly unstoppable force; construction and restoration are everywhere.

Increasing numbers of foreign investors are descending on Uruguay because of its stable government, the ease of doing business there and the automatic qualification for passports and citizenship, which the current government offers. A BBC article published last year http://www.bbc.co.uk touted Uruguay as popular with foreign investors looking for beach homes and colonial buildings, both of which are plentiful. However, certain areas, including much of Ciudad Viaje, are still works in progress; though fine to walk around during the day, it is largely a no-go zone at night once the offices have emptied.

Although Montevideo is minute in comparison with some of the mega-cities in neighbouring Brazil and Argentina, it is a delightful place to visit and definitely deserves to be visited. The centre, especially within a few blocks of Plaza Independencia and large sections of Ciudad Viaje (with the exception of the bleak sea front) are also worth exploring during the day.

The street markets, churches and plazas the most beautiful of which is Zabala make wonderful places to while away an afternoon. It is also possible to visit the Mausoleo Artigas, the point of the Plaza Independencia, built in memory of José Artigas who repelled Spanish invaders from 1811 before he was exiled to Paraguay where he died in 1850. Although Artigas’ actions did not completely end foreign intervention in the affairs of Uruguay (the region came under the control of Brazil until a coalition of Orientales and Argentine troops finally liberated the region in 1828).

Two notable museums include the Casa Rivera, which houses a fantastic collection of 18th century art displayed in moody burgundy rooms as well as some indigenous artefacts and the Museo Rómantico which contains a treasure trove of furniture, paintings, chandeliers, silverwear and crockery, as well as the personal belongings of wealthy European settlers.

After all that exploration we had worked up a considerable appetite and were very pleased to find that Montevideo delivered on the culinary front. Lunchtime is the best time to check out the plato del dia (set menu) offered at almost every establishment in town, these offers allow you to eat three courses, wine beer or a soft drink and tea or coffee incredibly cheaply. Perfect!

Cosy Colonia – Experiencing an Uruguayan Seaside Town

“If only we hadn’t indulged in that buffet breakfast…”

That was us on the ferry half way from Buenos Aires to Colonia del Sacramento in Uruguay. Murky, chocolate coloured Atlantic seawater was swilling around the ferry, forming waves that filled us with nausea. The breakfast, which had seemed like such a good idea earlier that morning, was threatening to come back to greet us, which was a concern as there was a distinct absence of sick bags on the vessel. Looking out the windows, as sky and sea rapidly exchanged places, made it difficult to do anything but grip the seat. The crew had put on a Shakira video which, presumably, was supposed to distract us during the choppy crossing. Our only comfort was the Schadenfreude of knowing that many other visitors would have opted for the better known ferry service operated by Buqebus, which takes 3 hours; triple the suffering of our express ferry.

Greeted by blustery weather when we docked at the small port in Colonia del Sacramento, we set about finding our lodgings for the night before exploring the beautiful cobbled streets and multi-coloured colonial buildings. It was easy to see why the town has become increasingly popular with Argentines wanting to escape the traffic and noise of Buenos Aires for the weekend, as well as Brazilians; on every street there was at least one colonial property for sale. This small town in Uruguay is the complete opposite of Buenos Aires with its calm pace and maté sipping residents it is a great place to get some sea air as you walk past the yachts in the harbour.

We were amazed at the Uruguayan (and to a lesser extent the Argentine and Paraguayan) love affair with yerba mate. Uruguayans sip this hot drink at every opportunity; it seems to be a national addiction. Many Uruguayans carry a thermos flask of hot water everywhere they go, so it is possible to top up the cup on a street corner, a park bench or while waiting for a bus. A kind of bitter green tea, it is brewed in small cups made of wood, or metal and often covered with leather and sipped through a silver ‘straw’ (aka bombilla). There are even specially made leather bags for transporting the paraphernalia and we frequently observed locals carrying two handbags: a mate bag and a normal handbag. That is what you call commitment to the habit, a habit which I could not imagine ever taking off in our throw away coffee cup, tin can and plastic bottle culture.

Ideal for exploring on foot, Colonia, as it is known by locals, is popular for its cafes and restaurants where it is possible to sample chivitos, the nation’s favorite snack. Thin steaks are piled on a bed of French fries and topped with eggs, salad or cooked vegetables and sometimes bread.

After two days of relaxation in Colonia, it was time to travel three hours across the lush green countryside to Montevideo, the capital of Uruguay, to check out what delights it had to offer.

A Tale of Two Argentinean Cities – Part Two Córdoba

We had heard that Córdoba is a favourite among ‘culture vultures’ and from the moment we arrived in the city we were impressed with its colonial architectural beauty, sophistication, myriad museums and galleries, and the contagious laid-back pace of this stunningly beautiful university town.

The University – Universidad National de Córdoba

Entering the site of the Jesuit school and university in the centre of the Old Town, we were transported back several hundred years during a brief tour, conducted by a current university student (the primary and secondary schools share the same site as the university).

This proud institution has been educating boys for 400 years (girls were only admitted recently) and still has classrooms equipped with antique desks and black boards, as well as a teacher’s room with a huge fireplace which you could literally walk into. The museum exhibited telescopes, globes and microscopes which were several hundred years old, it was very Hogwartseque.

Museo de la Memoria

The area surrounding the school was so lovely that it was almost inconceivable that one of the neighbouring buildings played a now infamous role in Argentina’s recent history. In the pedestrian zone photos of some of Argentina’s ‘disappeared’ strung up on cord between the buildings, flutter in the wind. The term ‘disappeared’ refers to the 30,000 people arrested by the military dictatorship which took control in the mid-1970s.

These ‘disappeared’ were targeted because they were suspected of being dissidents, having communist ties or having the misfortune to have known someone who came under the regime’s suspicion. We later found out that it was common to target all those people who were named or whose addresses or phone numbers appeared in the diaries and correspondence of those arrested. It was chilling to imagine living under such a government today – Imagine if every ‘friend’ you have on Facebook was targeted for disappearance? What would it be like if every person in your mobile phone book or Hotmail/ Gmail/ Yahoo! accounts could be tracked down and was arrested, tortured and killed for their perceived guilt by association?

Many of these people have not been seen since their arrests; their whereabouts continues to be a difficult theme in Argentinean politics, with the Madres de Mayo faithfully protesting outside the Casa Rosada in Buenos Aires every Thursday at 3:30 pm appealing for information on their children, whose bodies have yet to be found.

Many of these people have not been seen since their arrests; their whereabouts continues to be a difficult theme in Argentinean politics, with the Madres de Mayo faithfully protesting outside the Casa Rosada in Buenos Aires every Thursday at 3:30 pm appealing for information on their children, whose bodies have yet to be found.

At the Museo de La Memoria, which is housed in one of the former detention centres used for torturing and interrogating suspects, we were able to learn about the methods used by the military regime to repress opposition, as well as the underground attempts to circulate banned material, including communist publications and magazines which criticised the regime. The museum is small, and does not have any English explanations, but it is clear that a lot of thought has gone into creating this tribute to the ‘disappeared’ and is an important piece of the jigsaw which makes up modern Argentina.

At the Museo de La Memoria, which is housed in one of the former detention centres used for torturing and interrogating suspects, we were able to learn about the methods used by the military regime to repress opposition, as well as the underground attempts to circulate banned material, including communist publications and magazines which criticised the regime. The museum is small, and does not have any English explanations, but it is clear that a lot of thought has gone into creating this tribute to the ‘disappeared’ and is an important piece of the jigsaw which makes up modern Argentina.

Art and Architecture – Celebrating the Bicentenary of Cordóba

Córdoba is pleasant to walk around and has numerous plazas where you can relax either in the shadow of bicentennial commemorative hoops, fountains or statues of conquistadors. The city is brimming with beautifully maintained public spaces making it one of the pleasantest places we visited in Argentina.

It is also a great place to fuel up on excellent food which is reasonably priced (after all it is a university town) and good wine before heading on to the next museum, which for us was the Palacio Ferrerya and the Museo Provincial de Bellas Artes Emilio Caraffa.

Set in a lovely colonial house, which is itself a work of art, it is filled with the sculptures and paintings by Argentine artists. A small modern art installation, accessed by a staircase covered in metres of cow hide, is open on the top floor and is worth a peak, too.

Our only regret regarding Córdoba is that we did not have more time there. It literally oozes sophistication and with so much art and culture, we could easily have spent a week there. If we had to decide between Mendoza and Córdoba, the latter would win the contest every time!

A Tale of Two Argentinean Cities – Part One Mendoza

Consistently recommended by travellers we have met, Mendoza was high on our ‘must see’ list for Argentina. The Lonely Planet describes its reconstruction following the earthquake which devastated it in 1861 by stating that:

‘This was a tragedy for mendocinos (people from Mendoza), but rebuilding efforts created some of the cities [city’s] most-loved aspects: the authorities anticipated (somewhat pessimistically) the next earthquake by rebuilding the city with wide avenues (for the rubble to fall into) and spacious plazas (to use as evacuation points). The result is one of Argentina’s most seductive cities – a joy to walk around and stunningly picturesque.’

So you can imagine our disappointment when we instead found it was more 1970s dilapidated concrete prefab jungle than colonial architecture and spacious piazzas. Perhaps it was the autumnal weather, choking diesel fumes, the neglected pavements, or the forlorn fountain in Plaza Independencia; I am not really sure, but it was everything but picturesque. There were some nice vinotecas and restaurants, but McDonald’s and Carrefour were not seducing us.

Almost at the point of giving up on Mendoza, we decided to head out to the countryside to see what actually put Mendoza on the map for foreigners: its vineyards. Half an hour out of town by bus, the vineyards, olive groves and orchards surrounding Mendoza proved to be the perfect antidote.

Disembarking at the one street town of Maipú, we walked past barking dogs, shuttered houses and along sun baked dusty streets, where jalopies lazily rusting away. We were en route to our appointment for a wine tasting at the bodega La Rural when we got sidetracked by a sign advertising homemade chocolate and stumbled into a building owned by …. Who specialise in homemade chocolate, olive oil and preserves.

We spent the next half an hour (it would have been more but for the appointment) knocking back shots of their ‘Russian Death’ and Rose Schnaps; munching on olives as we learned about the different grades of olive oil; eating sundried tomatoes and indulging in teaspoonfuls of Dulce de Leche followed by homemade chocolate. Everything was delicious!

Realising that we were expected at the bodega imminently, we purchased a couple of jars of our favourite things (we would have purchased crates of stuff if we were not on such a long trip!) and jogged down the road to La Rural.

On entering the main building, we were transported to a bygone era of wine making; our guide took us through the museum which exhibits over 5000 items used in European and Argentinean viticulture over the last 500 years. The collection is the most important in the Americas. We also saw some of the cellars and toured the modern production facilities.

On entering the main building, we were transported to a bygone era of wine making; our guide took us through the museum which exhibits over 5000 items used in European and Argentinean viticulture over the last 500 years. The collection is the most important in the Americas. We also saw some of the cellars and toured the modern production facilities.

At the end of the fascinating free tour which had galloped through several centuries of wine making in Argentina and given us some background on the Italian founder of La Rural, don Filipe Rutini who established it in 1885, we tasted Museo, a wine which can only be sampled at La Rural’s bodega in Mendoza.

Walking past the sundried vines as we returned to the main road for the bus back, it became clear why a visit to Mendoza is high on many visitors’ lists. There are approximately fifteen bodegas, olive oil producers and family-run establishments producing everything from fine wines to chocolate in Maipú, making it a genuine foodie paradise. It would easily be possible to fill several days exploring it at leisure, it is well worth leaving the city for.

Chillin’ in Chile – Amusing Oneself when Stuck in Santiago

After 20 hours on a semi-cama bus, two three course meals, wine and enough sweet black coffee to induce involuntary spasms, we were finally at the border post between Argentina and Chile (3000m above sea level). In the freezing Immigration and Customs building we chatted to a lone South Korean backpacker, who was wearing flip-flops and no socks. Hopping from one foot to the other for half an hour in the early morning chill (none more enthusiastically than the Korean woman who was doing a cross between a child’s must-go-to-the-loo dance and the highland fling), we were getting used to waiting Latin American style.

After 20 hours on a semi-cama bus, two three course meals, wine and enough sweet black coffee to induce involuntary spasms, we were finally at the border post between Argentina and Chile (3000m above sea level). In the freezing Immigration and Customs building we chatted to a lone South Korean backpacker, who was wearing flip-flops and no socks. Hopping from one foot to the other for half an hour in the early morning chill (none more enthusiastically than the Korean woman who was doing a cross between a child’s must-go-to-the-loo dance and the highland fling), we were getting used to waiting Latin American style.

After all the passengers on the bus had been through Immigration, it was on to Customs and sniffer dogs searching for contraband: fruit, seeds, meat and fish as well as illegal substances which might be carried by ‘mules’. Everyone lined up with their luggage as police dogs and armed customs officers worked their way down the line. Suddenly, the dog was all over an American backpacker’s luggage. Her voice trembled as she tried to explain in Spanish that the bag, which the dog had taken a disconcerting interest in, was indeed hers. A short, but tense session of questioning ensued, followed by some rummaging in the bag and yet more questions. The other passengers were starting to get a little impatient; all eyes were on the young blonde. Was she going to get hauled away in handcuffs, never to be seen again? Once we heard Tienes miel en la mochilla? (Do you have honey in the backpack?), there was a collective sigh of relief: It would not be ‘snowing in the valley’ that morning, as they say in LA. Although she would have received a stiff fine if she had had honey in her baggage, we could all relax knowing that we did not have a smuggler in our midst. Finally, we re-boarded the bus and the American returned to her seat behind us. We never did find out what attracted the dog to her luggage.

Moments later we were meandering up and down serpentine roads, between spectacular mountains and past seemingly endless acres of autumnal vineyards beneath a perfectly cloudless sky. We basked in the perfect autumnal weather, unexpectedly breaking into a sweat as we shuffled between the subte and our hotel, bent double under the weight of our backpacks (Why are these bags almost back to their departure weight, even though we have given away several kilos of clothes since we left in January?). Little did we know, that the next morning we would awake to a light drizzle that was simultaneously manifesting itself as heavy snowfall in the mountains and would strand us in Santiago de Chile for almost five days.

The general consensus among backpackers is that the Santiago de Chile lacks the style of Buenos Aires. It is considered parochial in comparison; safe, but boring, rather like the Singapore of South American cities. While anecdotal evidence indicates hiking boots are de rigueur accessories for the Santiaguinos’ Winter 2011 wardrobe – something no self respecting porteño would be seen dead in – it is not all psychedelic Andean knitwear and sensible shoes.

There is nothing like being well and truly marooned in a city to give you the chance to see what it has to offer. Here are four quick tips for amusing yourself if you ever get stuck in Santiago:

Museo Chileno de Arte Precolombino

In inclement weather head straight here and step back several centuries. This museum contains a wonderfully presented collection of artefacts from various pre-colonial Latin American civilisations. Unlike many museums in Latin America, there has been a concerted effort to post good quality explanations in English which is rare.

Subway stations

You might not have heard, but Santiago’s subte is a work of art in itself. Several stations have murals which tell the story of the heroes of the independence movement or which have become forums for exhibiting modern art. This was one of our favourite stations ‘Universitad de Chile’ the artist is Mario Toral.

Colonial Architecture

If you want to get away from all the modern skyscrapers in the suburbs, head straight for the centre of town where you can see beautiful churches, the theatre and opera house. It is a lovely place to relax with a cortado and croissant.

Enjoy Andean scenery

Perhaps there are other ‘sky lounges’ which offer a good view of the Andes from the city, but it is hard to think of a more sophisticated setting than the Grand Hayatt Club Lounge from which to view the snow capped mountains which surround the city. While enjoying Chilean wines, smoked salmon and a variety of delicious snacks you can sit back in the warm glow of the softly lit lounge and watch the sun turn the mountains pink before the moon comes up to bathe them in its frosty beam.

Books on Africa – Our Top Picks

During our long travel days in Africa we had a lot of time to catch up on reading, and more specifically, to read about the continent which we were travelling through. Luckily, we were able to get our hands on some excellent titles which really helped us to delve deeper into the recent history of the continent, its current challenges and the possibilities which the future holds for the 1 Billion people who live in its 62 territories. Below we would like to recommend five of the best titles we read with you.

The Boy Who Harnessed the Wind – William Kamkwamba

The true story of a young Malawian boy whose scientific curiosity transforms the lives of his family and fellow villagers. After seeing a picture of a windmill in a science book, William begins a quest to build his very own turbine from scrap metal. This is a gripping account of triumph over adversity told with honesty and simplicity.

Six Months in Sudan: A Young Doctor in a War-torn Village – James Maskalyk

An excellent combination of blog, diary and personal reflections, this is the true story of a young Canadian doctor who decides to spend six months working at a rudimentary hospital in Abyei, Sudan with Médecins Sans Frontières. This is a warts and all account of working on the front line in a place which is off the radar for most westerners.

The Shadow of the Sun: My African Life – Ryszard Kapuscinski

An insightful collection of non-fiction accounts of the experiences of Poland’s only foreign correspondent in Africa in the 1950s-1980s. A great read if you want to dip into the varying cultures of Africa from Angola to Zanzibar and beyond.

When a Crocodile Eats the Sun – Peter Godwin

A history of modern Zimbabwe, interwoven with the biography of Godwin’s parents, who moved to Zimbabwe shortly after WWII. Godwin, a former National Geographic correspondent, charts the decline of the country over the past 50 years. The beauty of this book is its ability to use personal anecdotes to make the events of a distant, and largely forgotten, corner of Africa resonate so powerfully.

We Are All the Same: A Story of a Boy’s Courage and a Mother’s Love – James T. Wooten

This book tells the story of the AIDS epidemic in South Africa through the experiences of a young boy and his adoptive mother. In this short volume we learn an incredible amount about the two worlds which exist in modern South Africa: that of the rich and the poor, the sick and the healthy, the educated and the uneducated. A fantastic book which although sad, is ultimately inspiring.

Other Suggested Titles:

Ja, No, Man: Growing Up White in Apartheid-Era South Africa – Richard Poplak

We Wish to Inform You That Tomorrow We Will be Killed with Our Families – Philip Gourevitch

A Long Walk to Freedom: The Autobiography of Nelson Mandela – Nelson Mandela

Do They Hear You When You Cry? – Fauziya Kassindja

The theme tune of our journey through Africa:

Robben Island

From the top of Table Mountain, you can just make out Robben Island on a clear day. Named after the seals (‘Robben’ means seal in Dutch) which sailors from the Dutch East India Company hunted when they stopped there, it is probably one of the most famous places of exile because of the part it played in the story of Nelson Mandela and the end of Apartheid in South Africa.

Trawling our way across the choppy sea, which separates Cape Town from our mist shrouded destination, we had ample time to reflect on the psychological impact that banishment must have had on arriving inmates. As we drifted further out into the fog, Table Mountain vanished; the metaphor was not lost on us: we were bound for another world, a different reality.

Once our boat docked, we were directed to a bus and met Yasin Mohammed, our guide. Affable, witty and incredibly inspiring, Yasim, the former General Secretary of the Pan Africanist Congress, has guided Barack Obama, Hillary Clinton, Helmut Kohl, King Abdullah of Saudi Arabia and Bill Cosby around the island.

From the moment we met him, it was easy to understand why he has been the preferred guide for visiting dignitaries. When you visit such an infamous prison, a sight of oppression and the former stronghold of an illegitimate government, you do not expect to laugh until you cry, to be made aware of your country’s personal connection to the place, or to come away uplifted by the compassion that flows freely from a man who might just as easily have been religated to obscurity and twisted with bitterness.

Yasin charted the history of the island from its days as a leper colony, to its most famous incarnation as the maximum security prison for dissidents and anti-apartheid strugglers such as Robert Sobukwe, Nelson Mandela and Jacob Zuma. We learned how Sobukwe, founder of the PAC and leader of the Defiance Campaign in 1952, marched in opposition to the Pass Law, which required black South Africans to carry passes at all times and limited their freedom to travel within their own country. We heard about the three year sentence he received for marching to the local police station and handing in his pass, as well as his solitary confinement on Robben Island, which was so complete that it caused his vocal chords to atrophy rendering him almost mute on his release.

As we passed the church next to the former guards’ houses, we heard about the flagpole on top that announced the births of guards’ children: a pink flag was hoisted for a girl; a blue one for a boy. Yasin explained that Mandela had lamented the irony of celebrating the birth of a guard’s child when inmates could not even see their children until they were 18. He also recalled that Mandela’s greatest heartache was caused by a knock on his cell door one night, which announced the delivery of a letter informing Mandela that his eldest son had died in a car crash.

Elucidating the inmates’ philosophy of ‘The Three Ms’ (a combination of the teachings of Mahatma Ghandi, Martin Luther King and Nelson Mandela) he explained the reasoning behind non-violent protest, showing how these three positive role models provided hope to the political prisoners languishing in jail.

The ‘University of the Limestone Quarry’ was another way in which many political prisoners turned their hard labour in the prison’s quarry into a chance to develop themselves. The work was back breaking and caused snow blindness, because no sunglasses were allowed to be worn until two years before the end of apartheid (to this day, flash photography photos of Nelson Mandela are forbidden because his eyes were so badly damaged by the glare from the limestone). The prisoners used their days at the quarry to exchange knowledge and information, enabling many including Comrade Zuma, as the President is known here, to study for several university degrees. Educated inmates taught the illiterate prisoners thereby enabling them to realize their educational aspirations.

The importance of the ULQ is obvious when one considers that of 20 million blacks in Apartheid South Africa, only 10 were doctors and 1 was a dentist. Blacks were barred from becoming pharmacists or chemists; many were also unable to pursue such careers because they were denied even the most basic education.

Yasin pointed out that apartheid did not end once one was imprisoned. Born of a Tamil Sri Lankan mother, his ethnic background meant that he was not in the lowest category of prisoner. Unlike black inmates, he would have been given a pair of trousers to wear (blacks were forced to wear shorts and denied underwear or socks), his food rations would have been superior to those of his fellow black inmates (see the food rations below). However he explained that all his fellow inmates fought in every conceivable way to resist the regime’s attempts to fuel racial hatred among the inmates and to gain equality for all.

A hunger strike and intervention by the International Red Cross in 1974 marked the first tangible steps towards improvement in the prisoners’ conditions: the authorities finally issued sheets to inmates; beds replaced the sleeping mats (which were as rough as doormats used placed outside houses in Europe for wiping your shoes on), food rations improved and hot water was allowed for bathing.

The last section of our tour was directed by an ex-political prisoner, who arrived in 1977 when he was 19. He spent a decade there. Outside Nelson Mandela’s cell he told us a little about the tricks inmates used to communicate across the sections of the prison including concealing messages inside tennis balls, which were delivered by “accidentally” hitting the occasional ball over the wall during recreation.

At the end of the tour we heard that economic realities encourage many of the guides to work at the sight of their former torment : 43 % South Africans are unemployed, so every 6 tours create one job for a former inmate who might otherwise be unemployed.

Boarding the ferry back to Cape Town it was sobering to recall that Mandela has bid the island goodbye after 14 post release visits, the last of which was to light the Olympic torch. He does not ever intend to return again.

Getting to Cape Town the non-touristy way

After a three-day delay at the Namib-South African border, we were finally hurtling across South Africa en route to the vineyards and the preppy university town of Stellenbosch, which was full of chic restaurants, wine bars and nightclubs. Stellenbosch, the location of one of South Africa’s best universities, with its distinctly European architecture, looks and feels decidedly un-African.

Unfortunately, the delay on the Namibian-South African border had eaten into our time, so we had to move on earlier than we would have liked to reach Cape Town for our onward flight. So, on Sunday morning at 8 am, we found ourselves commuting to Cape Town by the metro with church goers, city workers, persistent snack vendors, a one-eyed homeless man, an elderly leper and a constant convoy of beggars.

I have to admit that I was ashamed of being nervous about taking the train, but standing on the chilly platform waiting for it to arrive, I caught myself scanning the assembling passengers for dodgy characters: people who might try to rob us; those getting to close for comfort; the tall man who had stared at us when we entered the station and seemed to have his hand buried in his pocket – did he have a weapon? Remembering movies like Tsotsi, the story of youths trying to make it in a township, I found my imagination running wild. We were two obvious misfits. Martin was the only white person on the whole train. What on earth were we doing here?

The train cost 7.5 Rand (1 USD), while transfers on backpacker buses average 300 Rand per person. Looking back, it is insane (and shameful) to think that fear makes many visitors pay almost 40 times as much to travel to Cape Town (we did not see, or hear of any other tourists using this train, nor was it mentioned as a possible means of transport anywhere in our guidebook). Sadly, this fear may also keep tourists stuck in a parallel universe, preventing them from meeting many black South Africans (besides the waiters in restaurants and hotel employees) or actually speaking to the ordinary people who actually make up 80% of the population.

Taking the train gave us a chance to peek into the parallel world of ordinary black South African commuters. The carriage was a bustling marketplace full of snack vendors; seats were constantly claimed and given up; passengers were busily texting; reading well worn copies of Die Bybel; listening to their iPods and talking to their fellow passengers. As the journey progressed, we remembered a Belgian guy, we met in Bangladesh, who told us that he had travelled around South Africa on local transport; white South Africans had been absolutely shocked and unable to comprehend why he wanted to do such a thing.

Taking the train gave us a chance to peek into the parallel world of ordinary black South African commuters. The carriage was a bustling marketplace full of snack vendors; seats were constantly claimed and given up; passengers were busily texting; reading well worn copies of Die Bybel; listening to their iPods and talking to their fellow passengers. As the journey progressed, we remembered a Belgian guy, we met in Bangladesh, who told us that he had travelled around South Africa on local transport; white South Africans had been absolutely shocked and unable to comprehend why he wanted to do such a thing.

After an hour, we finally pulled into Cape Town, an amazingly beautiful city, set against the stunning backdrop of Table Mountain. The sun was shining brightly and the city was abuzz with marathon runners completing the last leg of their 42.1 km ordeal. Within minutes our train journey was a memory; an experience dislocated from the touristy Cape Town which we had entered. Although Apartheid is officially over, and economists speak enthusiastically of ‘Black Diamonds’ (the emerging black middle-class), the reality of economic inequality quickly becomes obvious in Cape Town.

A walk through the heavily protected neighbourhoods at the foot of Table Mountain reveals hundreds of signs advertising the security companies which are responsible for protecting properties. Exterior walls are topped with barbed wire and every window is protected with bars; prominent ‘Beware of the Dog’ signs are ubiquitous. Here nobody walks; the streets are eerily pedestrian free. One wonders if any of these residents have ever travelled by train in their own city.

On Long St, popular for its boutiques, hotels, restaurants, cafes and bars, most of the black people we saw were homeless beggars; literally and metaphorically they were standing outside, staring in on another country, a country that has found it necessary to erect police security booths to protect tourists from them.

Much has been written about the impatience with which many South Africans anticipate substantial change in their country, especially with regard to basic living standards. A large proportion of the population of this emerging nation effectively languishes in the third world, while a minority live in separately in their protected first world. Although progress has undoubtedly been made since the end of Apartheid, the South Africans we spoke to agreed that the process of destructing the mental, social, economic, cultural and racial barriers which remain is far from over.

Little Deutschland – Discovering the remnants of German influence in Africa

Swakopmund, Namibia’s second city, is known for its Gemütlichkeit, German beer halls and German-speaking community, relics of the colonial period. We were more than a little excited by the prospect of decent German bread, Apfelstrudel, Bratwurst and beer which awaited us in this microcosm of Germany in this distant corner of Africa. Our three days in Swakopmund were spent recovering from the rigors of bush camping by enjoying some of the best South African wines, excellent cheeses and eating some amazing game including kudu and oryx steaks, which we highly recommend.

Situated on Namibia’s coast, Swakopmund is a pleasant seaside town popular with German holiday makers. Walking through the centre of town, you could be forgiven for thinking that you were in Germany, perhaps even somewhere in the former East Germany which has recently undergone a makeover. Along the seafront a number of ice-cream parlors serve up an amazing selection of flavours which you can eat while walking along the windswept beach or on the pier as you look back on the town and the sand dunes beyond.

Freshly painted colonial buildings sparkle in the sun – were it not for the giant palm trees lining every street, it could easily pass for a small German town. Hendrik Witbooi Strasse intersects with Rhode Allée and the Bismark Medical Centre is just down from the Hotel Prinzessin Ruprecht. More that 50 percent of titles in every bookshop we visited were German – one even had Thilo Sarrazin’s controversial ‘Deutschland schafft sich ab’ in the window!

Attracted to Namibia by the diamond reserves discovered in the Sperrgebiet, and prospect of securing a colonial prize for Germany, which arrived on the continent much later than other European colonial powers, the first German colonists of Namibia were able to make their fortunes in mining, .

It was surprising to see how strong the German influence in Swakopmund remains, especially given that Germany lost control of all its colonies after WWI in 1918. Sitting on the sundrenched patio of the Brauhaus we ordered (in German) Bratwurst, Schmorbraten, Sauerkraut and Rotkohl, washed down with Radlers and white wine. We found ourselves surrounded by local residents all of whom were German speakers. We heard that many Germans actually stayed in Namibia rather than retuning to Germany, which turned out to be a wise choice given what was to happen in Europe during WWII.

Cheating with Cheetahs

We had the opportunity to visit Kamanjab Cheetah Farm, a place where orphaned cheetahs are kept, and it is possible to stroke the ‘tame’ (if such a word can ever be correctly applied) cats. Before visiting we were quite sure that it would be a tacky, zoo-like experience, surely seeing cheetahs in such an environment was cheating? Shouldn’t they be viewed in the wild? Wrong. Our time there was one of the highlights of our entire trip to Africa, allowing us the opportunity to get an even closer view of one of Africa’s most magnificent cat species.

Arriving at Kamanjab we were confronted with a huge warning sign: WARNING: RING THE BELL! All eyes darted towards the lithe cheetah pacing back and forth behind the wire fence. Staring, pacing, prowling. Suddenly it dawned on us that the slightly muted sound of a boy racer’s suped up car engine was actually the sound produced by the deep vibration of the cheetah’s purr.

Marinus, one of the farm owner’s two sons, gave us a quick safety briefing before we entered the premises. He ran through a catalogue of don’ts: don’t touch their paws, don’t touch their tails and most important of all, if Marinus warned us to move away from a particular animal, we had to step away immediately.

When the gate was finally unbolted three cheetahs bounded excitedly towards us. Marinus led us around the back of the farmhouse as one of the three cheetahs trailed directly behind. It was deeply unnerving to be followed by an animal with the potential to kill.

In the garden we had the chance to stroke the cats as they lounged on the lawn. Terrified, I stroked a cheetah behind ears and felt the slightly rough fur on the back of its neck. There was a disconcerting power to vibrations beneath my fingertips as the cheetah purred with delight, meanwhile Martin was licked by the sandpaper tongue of another. When feeding time began each cheetah received its own hunk of meat, which it slowly devoured as we sat on the grass a couple of metres away, glad that none of us were on the menu today. Already the trip was proving more fascinating than we could ever have imagined, yet the best was still to come.

Piling into the back of one of the farm’s utility vehicles we drove into the wild cheetah farm enclosure located nearby. Here Marinus and his family were busy rearing cheetahs to be released into the wild in regions where the numbers were dangerously low. The Kamanjab Cheetah Park is one of several non-profit farms aiming to educate people in a bid to save this endangered species.

As we entered the sprawling estate a posse of cheetahs began to trail behind us. The setting sun was low in the sky and it was clear that they eagerly anticipated dinner. In the large plastic bin at the back of the vehicle we were carrying over 40 kg of meat to distribute to our hungry pursuers. When the lid was removed we could hear a laughably bird-like noise emanating from the waiting cats. All of us were taken aback by what sounded like a Velociraptor from Jurassic Park.

Hunks of meat were tossed from the back of the vehicle and it was interesting to note the solitary ceremony of eating, which began with a competitive leap into the air. Once the meat was secured, each cheetah would dart off to devour its portion in private behind a bush or under a tree. Once the last morsel had been retrieved we were left standing on our vehicle in the deceptively peaceful grass unable to identify a single one of the twenty or so cheetahs which had surrounded us only minutes before.

Natural Namibia – Beaches, Deserts and a Canyon

When Brad Pitt and Angelina Jolie chose the southern African nation as the birthplace for their first child, Namibia became front page news. Although it had long been a destination popular with Germans, playing host to a celebrity childbirth helped to put Africa’s youngest nation (until south Sudan is officially recognised) firmly on the safari and overlanding map. Now that the word is out, Namibia is fast becoming one of the most popular destinations in southern Africa.

Within 5 minutes of entering the country we were treated to the view of a male lion relaxing in the sun on the side of the road, followed by the rich wildlife of Etosha National Park the following day.

An abundance of colossal rock formations dot the Namibian countryside rearing up at the most unexpected intervals, they look as if they are transplants from Utah or parts of the Australian outback. This could easily be Marlboro country.

At Spitzkoppe in northern Namibia, we camped at the base of one of several red craggy peaks in the vicinity. When sunset came they glowed like red coals, blushing violently as the moon rose into the perfectly clear sky.

A day later, we were driving through peroxide blonde grassland and white sand contrasting starkly with the endless blue sky. It was here that we spotted our second African snake in the wild, a large black spitting cobra, slithering across the road. As our vehicle trundled past the Naja Nigricollis Woodi reared up at us inflating its hood. Though incredibly dangerous, the sight was strangely compelling; a stunning and contrast to the white glare of the sandy road.

Traversing the country we made our way to the Atlantic at a point where small white dunes tumble into the sea. It was hard to believe that just a month before we had been paddling in the Indian Ocean off Zanzibar on the other side of this vast continent.

Later we visited Cape Cross Seal Reserve a breeding ground for 50,000 seals which have commandeered the coastline (the stench was so awful that we got a nasal warning a couple of kilometres before we actually arrived at the site!).

Naukluft National Park must, however, take the award for the most impressive landscape we saw in the whole of Namibia, if not Africa. We camped just down the road from the gates so that we would be able to get in before the temperature soared. That morning, we carefully dragged our tent before putting it down so that we could dislodge any scorpions which might have been hiding under our warm groundsheet (after the spitting cobra and witnessing a scorpion being burned to death in the campfire by locals, we were beginning to take these precautions more seriously).

When the gate opened at 6:30 am we entered a wonderland of massive sand dunes of Sossusvlei. The dunes are static – the heavier sand which they are composed of means that they only move a few centimetres each year, rather than changing positions overnight as is possible in the Sahara. Some of them are over 300 metres and as we found out that morning, climbing them is exhausting work.

Our final destination in Namibia, before the Orange River and the ‘new’ South Africa, was Fish River Canyon. Although it is the world’s second biggest canyon, most people we have met have never heard of it. Unfortunately, a few fatal heart attacks and other emergencies heralded a decision by the authorities to ban day hikers, so we were not able to descend into the monumental chasm, but walking along the lip of the crater gave us a couple of hours to admire it from several angles.

If only we had had the good sense to stay there a day or two more rather than proceeding to the Orange River where we spent three days waiting for a permit to enter our final destination on the African continent, South Africa…

Back to Nature in the Okavango Delta

One of the highlights of a trip to Botswana is a trip on a makoro/ mokoro (dugout canoe) in the Okavango Delta. Everyone we met seemed to agree that it was magical being out in the middle of the Delta, away from light pollution, traffic and modern conveniences. Assured that one night would not be enough, we signed up for a two-night trip and entrusted ourselves into the hands of a man named Zero, who headed up the troupe of polers responsible for transporting us.

Our brief introduction to the polers was punctuated by a warning from Zero before we departed.

“Please, nobody jump out of the makoro if you see a spider, a dragonfly or a frog. I have had clients capsize the makoro before when they have seen these things…”

Little did we know that we were about to get up close and personal with countless species of spider that morning.

Forging our way through the reeds of the delta, like Moses in his basket, our bodies and faces were constantly whipped by rough grass which was home to an arachnophobe’s worst nightmare: white, black, brown and green spiders of all shapes and sizes, coming at your face, crawling over your legs and arms; blown back at you with swarms of other insects, as the dugout ploughed through the foliage.

Like gondoliers, the polers make the arduous task of propelling the dugout canoes through the water appear effortless. Gliding through papyrus choked channels and across lily ponds, they steer through crocodile infested waters and hippo bathing pools. Whenever we asked them whether we should be afraid of an attack they nonchalantly dismissed our concerns, pushing ever deeper into the labyrinth of papyrus reeds.

After three hours, we arrive sun-kissed and desperate for shade. The camp is situated on one of the larger islands in the Delta. Under a canopy of large shady trees we erected our tents, a bush toilet was dug and a fire lit. Water was boiled for tea and we broke out the lunch provisions before reclining in the shade to while away the hottest part of the day.

As the day passed, the sting of the midday sun subsided to be replaced by its milder incarnation. At four o’clock we departed for a bush walk, knowing that we were not guaranteed to see anything, but equally excited by the lion prints we discovered on the way and the copious elephant dung which Julius, our guide breaks apart for us to analyse. In hushed tones he explains the ecosystem in which we will reside for the next 48 hours in his heavily accented English. Sounding like an Irishman trying to pronounce the word ‘film’ Julius struggles with his double final consonants.

“Palumz and elephant tusuks” (palms and elephant tusks), featured heavily in his explanations along with the alarmingly named “wild beasts” (hopefully he was alluding to wildebeests!)

After we return to camp, an inky black darkness encompasses everything once the last embers of the fire burn out after supper. When we retire to our tents the shroud of darkness is heavy, pressing down on us from above, so opaque that it is impossible to see our hands raised directly in front of our faces. If you think about the darkness too much, you start to feel claustrophobic, the best way to quell the workings of an over-active imagination in this dark place, in the middle of nowhere, is to fall asleep quickly and pray that you will not need to search for ‘Dug’ (as we christened the shovel) en route to the hole-in-the-ground toilet during the night.

The second morning begins with another bush walk. While listening to Julius explain the principles of termite construction and the role of elephant dung in the germination of Delta coconut palms, we accidentally venture into the path of an animal which makes the guide and two scouts insist on an urgent retreat.

The day before, we had practised non-verbal signals for communicating danger, including the clicking of fingers, as well as the merits of running zig-zag when pursued by certain predators; today we were going to have to put everything learned into practice.