The highlight of any trip to Bolivia has to be the Salar de Uyuni. At 20,000 km² the world’s largest salt pan is an awesome sight to behold. A visit to Uyuni’s flooded salt pans, lakes and cacti covered islands will make you feel as if you have landed on another planet. Let the photos speak for themselves:

Latest

Digging in Potosi – The tale of dust, dynamite and Bolivian Whisky

Although the silver is depleted, the Cerro Rico is still being mined for composito a mixture of tin, mercury and other metals. Miners are organized in collectivos, i.e. they get together and work the mine as (in a way) entrepreneurs. This, however, happens with primitive technology: dynamite, pneumatic hammers (sometimes) and most commonly manpower. Many miners start working at the age of ~12, but do not live past 35 because of Silicosis, a lung infection caused by the excessive intake of dust that eventually destroys the lungs from the inside. Their fate is profoundly explored in the documentary ‘The Devil’s Miners‘ by Richard Ladkani and Kief Davidson, which follows two pre-pubescent brothers working in the Potosi mines.

Although the silver is depleted, the Cerro Rico is still being mined for composito a mixture of tin, mercury and other metals. Miners are organized in collectivos, i.e. they get together and work the mine as (in a way) entrepreneurs. This, however, happens with primitive technology: dynamite, pneumatic hammers (sometimes) and most commonly manpower. Many miners start working at the age of ~12, but do not live past 35 because of Silicosis, a lung infection caused by the excessive intake of dust that eventually destroys the lungs from the inside. Their fate is profoundly explored in the documentary ‘The Devil’s Miners‘ by Richard Ladkani and Kief Davidson, which follows two pre-pubescent brothers working in the Potosi mines.

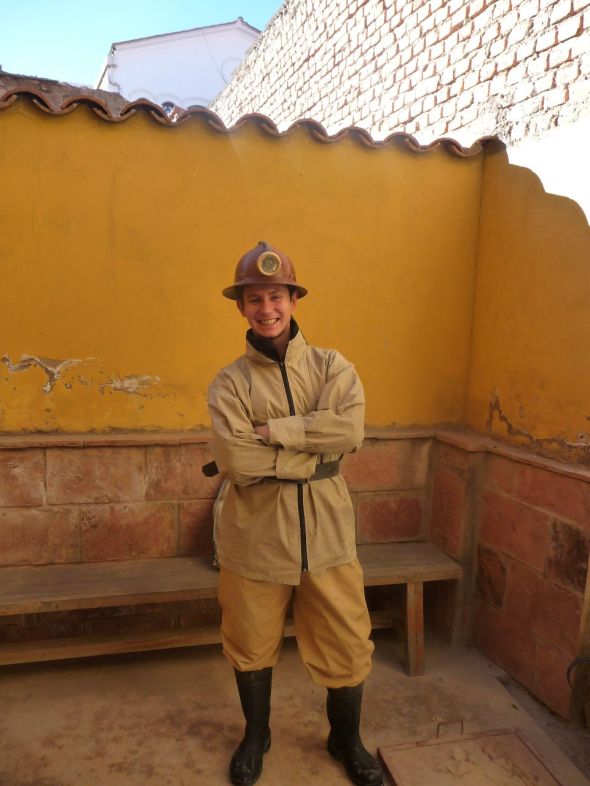

Although miners know that working in their mines will hasten their deaths they exhibit a certain pride in the fact that they are miners and that they are working for themselves. As I found out when I visited their mine, the most outstanding and breathtaking tourist attraction in Potosi. I explored an active shaft, saw the dynamite being planted and exploded, helped with drilling the dynamite holes and more. As this was not for the claustrophobic or faint hearted Michelle and I decided that I should have my boys’ adventure alone.

Although miners know that working in their mines will hasten their deaths they exhibit a certain pride in the fact that they are miners and that they are working for themselves. As I found out when I visited their mine, the most outstanding and breathtaking tourist attraction in Potosi. I explored an active shaft, saw the dynamite being planted and exploded, helped with drilling the dynamite holes and more. As this was not for the claustrophobic or faint hearted Michelle and I decided that I should have my boys’ adventure alone.

After getting our overalls, boots and hard hats, the tour started with the purchase of gifts for the miners: Bolivian whisky (98% alcohol), orange juice (to clear the throat after drinking the whisky), coca leaves (to numb hunger, thirst and fatigue), and gloves. Soon thereafter we drove to the entrance of the mine and descended down one of the many holes in the mountain.

After getting our overalls, boots and hard hats, the tour started with the purchase of gifts for the miners: Bolivian whisky (98% alcohol), orange juice (to clear the throat after drinking the whisky), coca leaves (to numb hunger, thirst and fatigue), and gloves. Soon thereafter we drove to the entrance of the mine and descended down one of the many holes in the mountain.

The rest of the tour was indescribable; something one has to experience on his /her own. Walking hunched through the tunnels, experiencing the noise of oxygen pumps, the mud, the dust and everything else constitutes an attack on the senses that most of us in the developed world rarely experience. Seeing the miners work with techniques that have been in use for 100 years or more is unbelievable.

The rest of the tour was indescribable; something one has to experience on his /her own. Walking hunched through the tunnels, experiencing the noise of oxygen pumps, the mud, the dust and everything else constitutes an attack on the senses that most of us in the developed world rarely experience. Seeing the miners work with techniques that have been in use for 100 years or more is unbelievable.

The tour is extremely immersive as tourist barriers or safety nets do not exist. Warped wooden planks are used as bridges over gaping holes that stretch into an indefinable darkness. Self-made ladders resembling those kids might make to access a tree house are standard, but only for a quarter of the way, for the rest you have to climb a rope. And every now and then you hear and feel the distant bass thump of a dynamite explosion, 5000 of which occur within the mountain every day.

The tour is extremely immersive as tourist barriers or safety nets do not exist. Warped wooden planks are used as bridges over gaping holes that stretch into an indefinable darkness. Self-made ladders resembling those kids might make to access a tree house are standard, but only for a quarter of the way, for the rest you have to climb a rope. And every now and then you hear and feel the distant bass thump of a dynamite explosion, 5000 of which occur within the mountain every day.

Miners sometimes put in shifts of 24h straight, in which they drill dynamite holes, fill them, explode the dynamite and take-out the composito mining carts, over and over again. The only way to survive this is alcohol and coca. All miners have a huge bubble on one of their cheeks, resembling some kind of terrible tumor. This is a bulk of coca leaves they suck on to suppress thirst, hunger and fatigue. Additionally, everybody is drinks alcohol on duty. We were also invited to partake in the consumption of Bolivian whisky whenever a group of miners took a break.

Miners sometimes put in shifts of 24h straight, in which they drill dynamite holes, fill them, explode the dynamite and take-out the composito mining carts, over and over again. The only way to survive this is alcohol and coca. All miners have a huge bubble on one of their cheeks, resembling some kind of terrible tumor. This is a bulk of coca leaves they suck on to suppress thirst, hunger and fatigue. Additionally, everybody is drinks alcohol on duty. We were also invited to partake in the consumption of Bolivian whisky whenever a group of miners took a break.

The highlight of the tour was actually drilling dynamite holes in a shaft using a pneumatic driller (an easy going 80kg heavy). Again the dust, noise and exertion cannot be described but have to be experienced. The only thing I can say is that we were absolutely exhausted after drilling 2 holes (which probably took us 15 minutes each), and now imagine that you have to do that day in, day out for several hours.

The highlight of the tour was actually drilling dynamite holes in a shaft using a pneumatic driller (an easy going 80kg heavy). Again the dust, noise and exertion cannot be described but have to be experienced. The only thing I can say is that we were absolutely exhausted after drilling 2 holes (which probably took us 15 minutes each), and now imagine that you have to do that day in, day out for several hours.

The tour closed with a visit to the Tio, who owns the Cerro Rico, this ‘devil’ is the invisible power that can take or spare lives when working in the mines. Consequently, all miners make sacrifices to the Tio and spill whisky on the ground every time they drink. This superstition is deeply rooted in the community and although they are Catholic, they believe that Jesus’s power does not extend underground beyond the mine entrance. This belief is comes from colonial times and was invented by the Spaniards who told indigenous people that they had to work otherwise the Dio would get them. Since in Quecha, the local language, no sound for ‘d’ exists the Dio became Tio.

Potosi – The town with a silver lining

As a teenager I had heard of the infamous mines of Potosi, where indigenous and African slaves were used to exploit silver for the Spanish crown. Being in Bolivia I convinced Michelle to seize the opportunity to visit this city.

As a teenager I had heard of the infamous mines of Potosi, where indigenous and African slaves were used to exploit silver for the Spanish crown. Being in Bolivia I convinced Michelle to seize the opportunity to visit this city.

Situated at around 4100m above sea level, Potosi is the highest city on earth, and thus it literally takes your breath away, due to the lack of oxygen. Despite a gradual ascent through the Andes, we struggled to walk 1 km with our backpacks on when we arrived – what usually might have taken 15 minutes, took the better part of 30. Afterwards, we tried to make the most of the remaining sunshine but had to retire to a restaurant to have food and catch our breath.

Although Potosi is not particularly large (~180.000 people), it has a rich history and beautiful colonial architecture as it was once one of the richest cities in the world. This wealth stemmed from the silver the Spaniards extracted from the Cerro Rico (rich mountain) after colonizing this region. During 1556-1783 a total of 41.000 tons of silver were extracted in Potosi alone. Thus it became a magnet for adventurers, New World aristocrats, and artists, all seeking to benefit from the riches of Potosi and its population swelled to more than 200.000 (comparable to the size of London at that time). The fact that a whooping 86 churches were built in that period is another sign of that wealth.

By 1825 the silver was almost depleted and the population sank to a mere 10.000. In a way Potosi could be compared to places like Dubai, or Qatar, that achieved extreme riches because of a natural resource, and thus became a magnet for people from all over the world, but eventually faced the threat of obscurity once the resource was depleted. The only hope of the UAE and states like it is to successfully reinvent itself.

Another breathtaking site and hint of former wealth in Potosi is the Casa Nacional de la Moneda. Praised by the Lonely Planet as “being worth its weight in silver”, it is housed in one the largest colonial buildings in Bolivia, and was formerly used as a mint.

It displays colonial art, silver coins and silverware, as well as the different technologies used to process silver. Two coins displayed in the museum are from a galleon, the Nuestra Senore de Atocha, that sank off the coast of Florida in the US en route to Spain in 1622 and was discovered by the Americans in 1985. It was filled with silver bars and coins worth 440 million USD. Unfortunately, Bolivia, South America’s poorest country, only received a meager ‘donation’ of two coins, both of which are now on display in the museum.

This silver has another even darker side: The suffering and deaths of the indigenous and black African slaves used to extract the silver from the mines of Potosi. Spaniards never actually entered the mines, or got their hands dirty, instead they used a system of forced labour called mita, in which Indigenas were forced to ‘donate’ two months of the year to work in the mines. Sometimes these two months turned into four or six months, or as long as one survived. Forced to work shifts of 16h hours, with nothing but their bare hands, or primitive tools, some did not see daylight for days and most did not survive long. An estimated 8 million people are thought to have died in the mines of Potosi; the primitive conditions, use of child labor and deaths continue to this day.

Visiting the Mennonite Communities in Filadelfia, Paraguay

On discovering that there was a German speaking community of Mennonites living in the middle of the Chaco we simply had to visit. Getting to Filadelfia, the largest and most important of the Mennonite communities in the Chaco, is easier today now that there are two buses a day which make the eight hour journey from Asunción, the capital of Paraguay. However, even a brief glance at the map will show that Filadelfia really is in the middle of nowhere; the journey reinforces this in the mind of the every passenger as the bus bumps its way along the sandy road bordered one either side by unbroken Chaco and few inhabitants as far as the eye can see.

On discovering that there was a German speaking community of Mennonites living in the middle of the Chaco we simply had to visit. Getting to Filadelfia, the largest and most important of the Mennonite communities in the Chaco, is easier today now that there are two buses a day which make the eight hour journey from Asunción, the capital of Paraguay. However, even a brief glance at the map will show that Filadelfia really is in the middle of nowhere; the journey reinforces this in the mind of the every passenger as the bus bumps its way along the sandy road bordered one either side by unbroken Chaco and few inhabitants as far as the eye can see.

Who were the Mennonite settlers who settled in this ‘Green Hell’? There are actually two main groups which belong to the Mennonite community in Paraguay: The first is comprised of pacifist Christians of German descent, who moved to Paraguay from Canada in the 1920s; they wanted to maintain their religious freedom and the ability to educate their children in German, rather than in English as the government of the time had requested. The other group was made up of the descendents of Russians who first fled the upheavals of Bolshevik Russia and Stalin’s subsequent purges. One Mennonite we met told us the story of her deaf father who had escaped Russia with her mother and made the long journey to Paraguay in search of a better life.

Who were the Mennonite settlers who settled in this ‘Green Hell’? There are actually two main groups which belong to the Mennonite community in Paraguay: The first is comprised of pacifist Christians of German descent, who moved to Paraguay from Canada in the 1920s; they wanted to maintain their religious freedom and the ability to educate their children in German, rather than in English as the government of the time had requested. The other group was made up of the descendents of Russians who first fled the upheavals of Bolshevik Russia and Stalin’s subsequent purges. One Mennonite we met told us the story of her deaf father who had escaped Russia with her mother and made the long journey to Paraguay in search of a better life.

At the Jakob Unger Museum on Ave Hindenburg it is possible to see some of the numerous items which settlers brought from Europe to Paraguay and to see photos depicting the conditions under which they lived in the first decades after the settled. Other items of interest include an example coffin made from a hollowed out tree trunk, the printing press used to produce the local newspaper and money from the period of the early waves of immigration. In a separate building an impressive collection of taxidermy including a puma, an anteater, local birds and reptiles is also on display.

At the Jakob Unger Museum on Ave Hindenburg it is possible to see some of the numerous items which settlers brought from Europe to Paraguay and to see photos depicting the conditions under which they lived in the first decades after the settled. Other items of interest include an example coffin made from a hollowed out tree trunk, the printing press used to produce the local newspaper and money from the period of the early waves of immigration. In a separate building an impressive collection of taxidermy including a puma, an anteater, local birds and reptiles is also on display.

Like the first settlers in America, the Mennonites were attracted by the opportunity for self determination and the chance to cultivate land which they received from the Paraguayan government. Photos in the Koloniehaus, which now houses the Jakob Unger Museum, document the history of the Mennonites – proud Europeans wearing the unsuitable winter garments as they pose for photographs in the overgrown Chaco. The tropical heat, disease carrying mosquitoes, snakes, pumas and jaguars as well as the lack of potable water must quickly have put the notion that they had reached the promised land out of their heads – over time they dubbed the Chaco the ‘Green Hell’ because of its razor sharp vegetation, which, if not carefully removed, could cause desertification, rendering the land useless. Another issue was the extreme temperature fluctuations which the region is prone to.

To this day, although the Chaco covers more than two thirds of Paraguay, only 2.5 % of the population currently reside there. However, with the completion of the Trans-Chaco Highway, which now provides a vital link to neighbouring Bolivia, tourists and job seekers from other parts of the country, as well as those looking to escape the drug-fuelled crime in eastern Paraguay have started arriving. Previously, there was limited contact with the outside world: Paraguayans did not choose to visit this inhospitable environment – this was a place of exile for opponents of the government and the location of the Chaco War, but aside from that the settlers managed to maintain a traditional lifestyle in keeping with their beliefs and values.

To this day, although the Chaco covers more than two thirds of Paraguay, only 2.5 % of the population currently reside there. However, with the completion of the Trans-Chaco Highway, which now provides a vital link to neighbouring Bolivia, tourists and job seekers from other parts of the country, as well as those looking to escape the drug-fuelled crime in eastern Paraguay have started arriving. Previously, there was limited contact with the outside world: Paraguayans did not choose to visit this inhospitable environment – this was a place of exile for opponents of the government and the location of the Chaco War, but aside from that the settlers managed to maintain a traditional lifestyle in keeping with their beliefs and values.

On arrival in Filadelfia, it is easy to see why poorer Paraguayans are attracted to the Germanic order of Filadelfia with its rubbish free streets, which lack the ubiquitous stray dogs seen in other large towns; the grid-like plan of the town with its wide roads, large houses and prosperous farms makes for a strikingly calm contrast to Asunción and Encarnation.

On arrival in Filadelfia, it is easy to see why poorer Paraguayans are attracted to the Germanic order of Filadelfia with its rubbish free streets, which lack the ubiquitous stray dogs seen in other large towns; the grid-like plan of the town with its wide roads, large houses and prosperous farms makes for a strikingly calm contrast to Asunción and Encarnation.

In town the contrast between the cars and houses of the Mennonites compared with those of the indigenous people as well as the wealth of supplies available at the Fernheim co-operative supermarket, as opposed to the basic staples on offer in the shops owned frequented by the indigenous population are reminders of how unequal the wealth distribution in the area is. When questioned about this the German Mennonites we talked to argued that their parents and grandparents had come to this place which nobody else had wanted to inhabit and created all of their wealth from scratch.

In town the contrast between the cars and houses of the Mennonites compared with those of the indigenous people as well as the wealth of supplies available at the Fernheim co-operative supermarket, as opposed to the basic staples on offer in the shops owned frequented by the indigenous population are reminders of how unequal the wealth distribution in the area is. When questioned about this the German Mennonites we talked to argued that their parents and grandparents had come to this place which nobody else had wanted to inhabit and created all of their wealth from scratch.

The curator of the Jakob Unger Museum and a local shop keeper explained (in excellent German) that the recent interest that Filadelfia has attracted has not necessarily been positive. There is concern that limited availability of jobs may lead to crime and other social problems, they also mentioned that although most of the community is now fluent in Spanish, in order to maintain their culture and traditions they would like to employ people who speak German. Given that the number of tourists who visit the area is relatively small, they are not seen as posing a threat to the Mennonite way of life. If one looks at the way people dress, observes the strikingly blonde Mennonite teenagers making their way to and from school and watches the local TV stations (which include live broadcasts of cattle auctions from around the country!), is clear that Filadelfia is being increasingly influenced by the outside world.

Five Things You Probably Didn’t Know About Paraguay

Paraguay? Why Paraguay? It seems that everyone you tell asks those two questions at some point because the general consensus among travellers in South America seems to be that Paraguay, rather like Suriname and the Guyanas is of minimal importance in comparison with other countries on the continent because it lacks major attractions such as Machu Picchu, Salar de Uyuni or Buenos Aires.

1. Paraguay is the second poorest country on the continent after Bolivia and the gap between the wealthy and the rest is quite striking. Driving through the country it is possible to see palatial villas and brand new SUVs, which contrast starkly with the rickety public transport system and the large number of buildings which look ripe for demolition. The unequal distribution of wealth in the country has also been the cause of land seizures by indigenous groups.

2. Like us you may find Paraguayans pretty difficult to understand because they seem to mix their Spanish and Guaraní in conversation (this mixture is known as Jopará). Among the Mennonite communities in the Chaco, German (Hochdeutsch and Plattdeutsch) is still spoken.

3. Paraguay is home to Trinidad and Jesús, two of the least visited Unesco World Heritage Sites on the continent. Trinidad is the best preserved of the two sites and is easily visited by bus from Encarnatión. The Jesuit ruins are set on a lush green hill in the middle of a small village and because there are so few visitors you can pretty much have the whole place to yourself.

4. The world’s largest water reserve, the Acuifero Guaraní, lies under Paraguay (and parts of Brazil and Argentina) and the Chaco, also known as the ‘Green Hell’, makes up more that 60% of Paraguayan territory, however less than 3% of the population lives there, most of whom are indigenous, as well as the descendents of Canadian and Ukrainian-German Mennonites.

4. The world’s largest water reserve, the Acuifero Guaraní, lies under Paraguay (and parts of Brazil and Argentina) and the Chaco, also known as the ‘Green Hell’, makes up more that 60% of Paraguayan territory, however less than 3% of the population lives there, most of whom are indigenous, as well as the descendents of Canadian and Ukrainian-German Mennonites.

5. In recent years Paraguay has attracted interest from outsiders because of its reputation for producing beef (as we learned when we turned on the TV one day to find that there was a channel dedicated to cattle news and broadcasting auctions!) and for the potential profits which soybean farmers, who are facing increasing prices for arable land in Argentina and Brazil, hope to make by relocating there. President George W. Bush Jr. is also rumored to have purchased an estate in the country in 2006.

5. In recent years Paraguay has attracted interest from outsiders because of its reputation for producing beef (as we learned when we turned on the TV one day to find that there was a channel dedicated to cattle news and broadcasting auctions!) and for the potential profits which soybean farmers, who are facing increasing prices for arable land in Argentina and Brazil, hope to make by relocating there. President George W. Bush Jr. is also rumored to have purchased an estate in the country in 2006.

Four Left Feet: Sometimes It Takes More Than Two To Tango…

It seems like just yesterday that we were standing on the border between Thailand and Laos trying to get a lift into town with a local who we had mistaken for a taxi driver. That was January, now suddenly it was the end of June. Out of the blue, my birthday had snuck up on me, on us, and so Martin was tasked with trying to make one particular day in what felt like and endless string of memorable days even more special. So what did he do? He decided to book a tango lesson.

It seems like just yesterday that we were standing on the border between Thailand and Laos trying to get a lift into town with a local who we had mistaken for a taxi driver. That was January, now suddenly it was the end of June. Out of the blue, my birthday had snuck up on me, on us, and so Martin was tasked with trying to make one particular day in what felt like and endless string of memorable days even more special. So what did he do? He decided to book a tango lesson.

I must admit that on hearing that my birthday present was going to include a dancing lesson I was tempted to protest, to feign illness, arrive late, or to do all three. I kept mentally fast-forwarding to a mirrored dance studio, which magnified my every mistake. I imagined an over eager teacher chastising me for not being able to replicate the arrogant elegance of the tango and disapproving of my flat pumps. My trepidation, which must emanate from a suppressed childhood ballet trauma, was palpable, but I need not have worried.

Our tango lesson at Complejo Tango turned out to be one of the most hilarious things I have done in a long time. The class had an unusually large number of male participants including a rugby team which was on tour in Argentina. Our effeminate instructor wasted no time whipping the motley crew of would be tango dancers into shape. The group included a trio of Japanese women in hiking boots, a rugby player in a bright pink pair of pyjamas who appeared to have lost a bet with the boys, and several haughty Brazilians, who were clearly perplexed by the lack of rhythm emanating from certain corners of the room.

Our tango lesson at Complejo Tango turned out to be one of the most hilarious things I have done in a long time. The class had an unusually large number of male participants including a rugby team which was on tour in Argentina. Our effeminate instructor wasted no time whipping the motley crew of would be tango dancers into shape. The group included a trio of Japanese women in hiking boots, a rugby player in a bright pink pair of pyjamas who appeared to have lost a bet with the boys, and several haughty Brazilians, who were clearly perplexed by the lack of rhythm emanating from certain corners of the room.

Most of us spent the entire hour crying with laughter, as our instructor critiqued our attempts to repeat the steps and tried to resist the temptation to smile when mimicking the sultry poses which tango demands.

By the end of the lesson all the women had learned to surrender into the arms of their male partners and a photo session ensued in which we attempted to capture high kicks, arched backs and head rush inducing positions on camera.

By the end of the lesson all the women had learned to surrender into the arms of their male partners and a photo session ensued in which we attempted to capture high kicks, arched backs and head rush inducing positions on camera.

Next, it was off to a three course dinner with copious amounts of wine from Mendoza, followed by a show performed by professional tango dancers. The show took us on a jaunt through the history and development of tango from its early origins to its current day revival. The live band featured haunting violins, an accordion and a perfectly postured pianist who played various styles of tango music over the next hour and a half.

Next, it was off to a three course dinner with copious amounts of wine from Mendoza, followed by a show performed by professional tango dancers. The show took us on a jaunt through the history and development of tango from its early origins to its current day revival. The live band featured haunting violins, an accordion and a perfectly postured pianist who played various styles of tango music over the next hour and a half.

The spinning, flipping and high kicks were effortlessly executed, but knowing how difficult it had been for all of us to master the most basic of tango steps, such as the ochos (named after the number eight in Spanish because it requires the female to make move in a figure of eight), we watched as the dancers with respect and envy as they glided athletically across the stage, changing costumes and scenes countless times to perform an awe inspiring show.

The spinning, flipping and high kicks were effortlessly executed, but knowing how difficult it had been for all of us to master the most basic of tango steps, such as the ochos (named after the number eight in Spanish because it requires the female to make move in a figure of eight), we watched as the dancers with respect and envy as they glided athletically across the stage, changing costumes and scenes countless times to perform an awe inspiring show.

Urban Uruguay – Uncovering the Most Underrated Capital City in the Region

Montevideo is an odd mix of beautiful plazas and pedestrian zones abutting some seriously depressed neighbourhoods. These multifaceted neighbourhoods host corporate offices, government buildings and the derelict graffiti covered relics of colonial splendor. In Ciudad Viaje, the graffiti is an incoherent salute to the poor and a desperate cry for liberation from gentrification, a ubiquitous and seemingly unstoppable force; construction and restoration are everywhere.

Montevideo is an odd mix of beautiful plazas and pedestrian zones abutting some seriously depressed neighbourhoods. These multifaceted neighbourhoods host corporate offices, government buildings and the derelict graffiti covered relics of colonial splendor. In Ciudad Viaje, the graffiti is an incoherent salute to the poor and a desperate cry for liberation from gentrification, a ubiquitous and seemingly unstoppable force; construction and restoration are everywhere.

Increasing numbers of foreign investors are descending on Uruguay because of its stable government, the ease of doing business there and the automatic qualification for passports and citizenship, which the current government offers. A BBC article published last year http://www.bbc.co.uk touted Uruguay as popular with foreign investors looking for beach homes and colonial buildings, both of which are plentiful. However, certain areas, including much of Ciudad Viaje, are still works in progress; though fine to walk around during the day, it is largely a no-go zone at night once the offices have emptied.

Although Montevideo is minute in comparison with some of the mega-cities in neighbouring Brazil and Argentina, it is a delightful place to visit and definitely deserves to be visited. The centre, especially within a few blocks of Plaza Independencia and large sections of Ciudad Viaje (with the exception of the bleak sea front) are also worth exploring during the day.

The street markets, churches and plazas the most beautiful of which is Zabala make wonderful places to while away an afternoon. It is also possible to visit the Mausoleo Artigas, the point of the Plaza Independencia, built in memory of José Artigas who repelled Spanish invaders from 1811 before he was exiled to Paraguay where he died in 1850. Although Artigas’ actions did not completely end foreign intervention in the affairs of Uruguay (the region came under the control of Brazil until a coalition of Orientales and Argentine troops finally liberated the region in 1828).

Two notable museums include the Casa Rivera, which houses a fantastic collection of 18th century art displayed in moody burgundy rooms as well as some indigenous artefacts and the Museo Rómantico which contains a treasure trove of furniture, paintings, chandeliers, silverwear and crockery, as well as the personal belongings of wealthy European settlers.

After all that exploration we had worked up a considerable appetite and were very pleased to find that Montevideo delivered on the culinary front. Lunchtime is the best time to check out the plato del dia (set menu) offered at almost every establishment in town, these offers allow you to eat three courses, wine beer or a soft drink and tea or coffee incredibly cheaply. Perfect!

Cosy Colonia – Experiencing an Uruguayan Seaside Town

“If only we hadn’t indulged in that buffet breakfast…”

That was us on the ferry half way from Buenos Aires to Colonia del Sacramento in Uruguay. Murky, chocolate coloured Atlantic seawater was swilling around the ferry, forming waves that filled us with nausea. The breakfast, which had seemed like such a good idea earlier that morning, was threatening to come back to greet us, which was a concern as there was a distinct absence of sick bags on the vessel. Looking out the windows, as sky and sea rapidly exchanged places, made it difficult to do anything but grip the seat. The crew had put on a Shakira video which, presumably, was supposed to distract us during the choppy crossing. Our only comfort was the Schadenfreude of knowing that many other visitors would have opted for the better known ferry service operated by Buqebus, which takes 3 hours; triple the suffering of our express ferry.

Greeted by blustery weather when we docked at the small port in Colonia del Sacramento, we set about finding our lodgings for the night before exploring the beautiful cobbled streets and multi-coloured colonial buildings. It was easy to see why the town has become increasingly popular with Argentines wanting to escape the traffic and noise of Buenos Aires for the weekend, as well as Brazilians; on every street there was at least one colonial property for sale. This small town in Uruguay is the complete opposite of Buenos Aires with its calm pace and maté sipping residents it is a great place to get some sea air as you walk past the yachts in the harbour.

We were amazed at the Uruguayan (and to a lesser extent the Argentine and Paraguayan) love affair with yerba mate. Uruguayans sip this hot drink at every opportunity; it seems to be a national addiction. Many Uruguayans carry a thermos flask of hot water everywhere they go, so it is possible to top up the cup on a street corner, a park bench or while waiting for a bus. A kind of bitter green tea, it is brewed in small cups made of wood, or metal and often covered with leather and sipped through a silver ‘straw’ (aka bombilla). There are even specially made leather bags for transporting the paraphernalia and we frequently observed locals carrying two handbags: a mate bag and a normal handbag. That is what you call commitment to the habit, a habit which I could not imagine ever taking off in our throw away coffee cup, tin can and plastic bottle culture.

Ideal for exploring on foot, Colonia, as it is known by locals, is popular for its cafes and restaurants where it is possible to sample chivitos, the nation’s favorite snack. Thin steaks are piled on a bed of French fries and topped with eggs, salad or cooked vegetables and sometimes bread.

After two days of relaxation in Colonia, it was time to travel three hours across the lush green countryside to Montevideo, the capital of Uruguay, to check out what delights it had to offer.

A Tale of Two Argentinean Cities – Part Two Córdoba

We had heard that Córdoba is a favourite among ‘culture vultures’ and from the moment we arrived in the city we were impressed with its colonial architectural beauty, sophistication, myriad museums and galleries, and the contagious laid-back pace of this stunningly beautiful university town.

The University – Universidad National de Córdoba

Entering the site of the Jesuit school and university in the centre of the Old Town, we were transported back several hundred years during a brief tour, conducted by a current university student (the primary and secondary schools share the same site as the university).

This proud institution has been educating boys for 400 years (girls were only admitted recently) and still has classrooms equipped with antique desks and black boards, as well as a teacher’s room with a huge fireplace which you could literally walk into. The museum exhibited telescopes, globes and microscopes which were several hundred years old, it was very Hogwartseque.

Museo de la Memoria

The area surrounding the school was so lovely that it was almost inconceivable that one of the neighbouring buildings played a now infamous role in Argentina’s recent history. In the pedestrian zone photos of some of Argentina’s ‘disappeared’ strung up on cord between the buildings, flutter in the wind. The term ‘disappeared’ refers to the 30,000 people arrested by the military dictatorship which took control in the mid-1970s.

These ‘disappeared’ were targeted because they were suspected of being dissidents, having communist ties or having the misfortune to have known someone who came under the regime’s suspicion. We later found out that it was common to target all those people who were named or whose addresses or phone numbers appeared in the diaries and correspondence of those arrested. It was chilling to imagine living under such a government today – Imagine if every ‘friend’ you have on Facebook was targeted for disappearance? What would it be like if every person in your mobile phone book or Hotmail/ Gmail/ Yahoo! accounts could be tracked down and was arrested, tortured and killed for their perceived guilt by association?

Many of these people have not been seen since their arrests; their whereabouts continues to be a difficult theme in Argentinean politics, with the Madres de Mayo faithfully protesting outside the Casa Rosada in Buenos Aires every Thursday at 3:30 pm appealing for information on their children, whose bodies have yet to be found.

Many of these people have not been seen since their arrests; their whereabouts continues to be a difficult theme in Argentinean politics, with the Madres de Mayo faithfully protesting outside the Casa Rosada in Buenos Aires every Thursday at 3:30 pm appealing for information on their children, whose bodies have yet to be found.

At the Museo de La Memoria, which is housed in one of the former detention centres used for torturing and interrogating suspects, we were able to learn about the methods used by the military regime to repress opposition, as well as the underground attempts to circulate banned material, including communist publications and magazines which criticised the regime. The museum is small, and does not have any English explanations, but it is clear that a lot of thought has gone into creating this tribute to the ‘disappeared’ and is an important piece of the jigsaw which makes up modern Argentina.

At the Museo de La Memoria, which is housed in one of the former detention centres used for torturing and interrogating suspects, we were able to learn about the methods used by the military regime to repress opposition, as well as the underground attempts to circulate banned material, including communist publications and magazines which criticised the regime. The museum is small, and does not have any English explanations, but it is clear that a lot of thought has gone into creating this tribute to the ‘disappeared’ and is an important piece of the jigsaw which makes up modern Argentina.

Art and Architecture – Celebrating the Bicentenary of Cordóba

Córdoba is pleasant to walk around and has numerous plazas where you can relax either in the shadow of bicentennial commemorative hoops, fountains or statues of conquistadors. The city is brimming with beautifully maintained public spaces making it one of the pleasantest places we visited in Argentina.

It is also a great place to fuel up on excellent food which is reasonably priced (after all it is a university town) and good wine before heading on to the next museum, which for us was the Palacio Ferrerya and the Museo Provincial de Bellas Artes Emilio Caraffa.

Set in a lovely colonial house, which is itself a work of art, it is filled with the sculptures and paintings by Argentine artists. A small modern art installation, accessed by a staircase covered in metres of cow hide, is open on the top floor and is worth a peak, too.

Our only regret regarding Córdoba is that we did not have more time there. It literally oozes sophistication and with so much art and culture, we could easily have spent a week there. If we had to decide between Mendoza and Córdoba, the latter would win the contest every time!